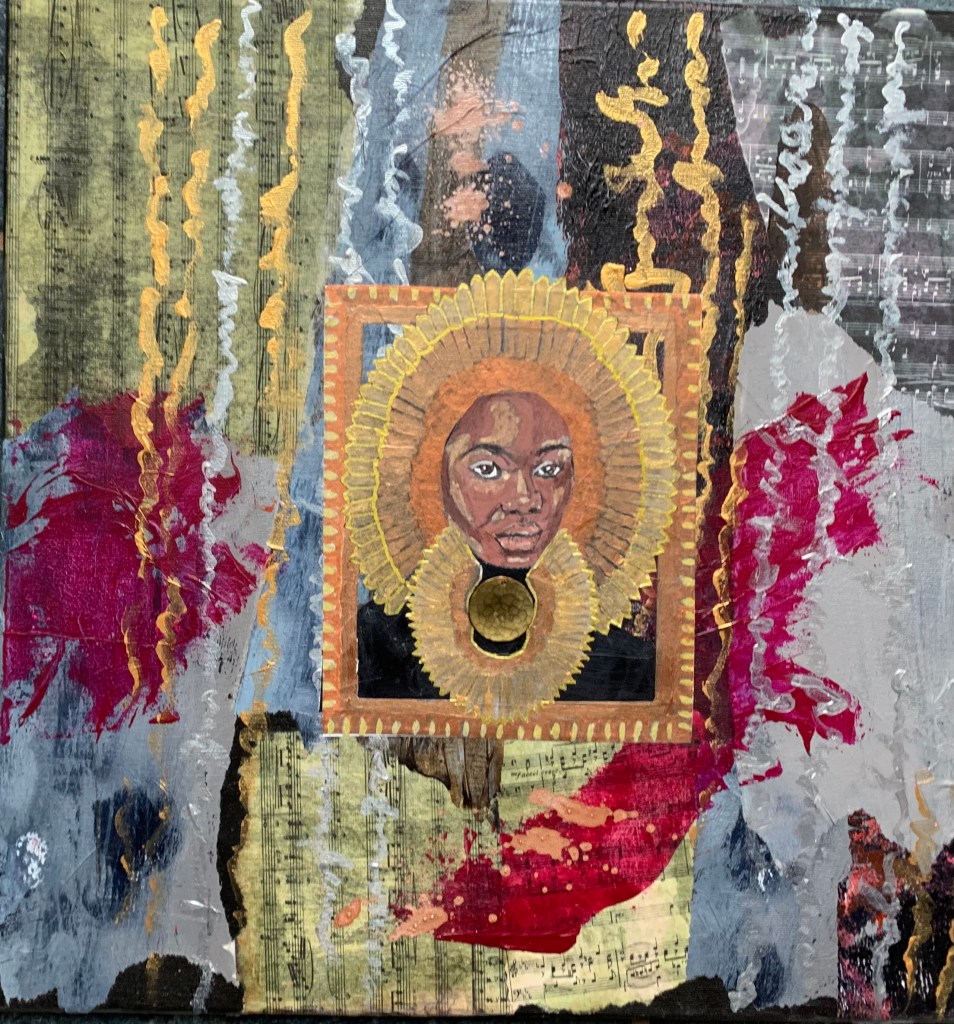

I think that one can live one’s life in black and white where things are right or wrong, good or bad, sacred or profane; if it’s not the one, it’s the other. Or I one can live life in colors that mirror the splendor of the sun’s rising and setting, the hues of plants and trees and flowers, the pallets of character and feeling set up in the human heart to paint one’s days. In my living room are hanging the paintings I have completed in the past four years showing my development as an artist. But my life has its own gallery of days. There are some times that are not very skillful but filled with the childhood exuberance of feeling the sheer joy of smearing paint with my fingers across slick paper. Then there are drawings of days when the lines did not connect of complementary colors that mixed to mud on the page when I was trying to be loved in the only way I knew how and messing things up royally. But in walking the halls of this gallery, I see days now with beauty that I once thought to be only ugliness, strengths that I thought were weakness, and joy in my deepest sorrows. It has not been a black and white life. These two new paintings reflect what I hope will be the remainder of my days.