I.

Once shocks had cured and dried in contours of time;

this field had gathered whiles of corn in long,

curved rows. But the war and the drought of men ended.

Flash floods of housing ran off down this hill

in torrents, puddled into close, brick queues

and cement alleys with iron-barred storm drains,

the teeth of Moloch we as children fed

with relinquished sneakers, stuck like virgins bound

for the deep, wet furnace that fed Herring Run.

These alleys are my wilderness of dragon’s teeth

and cracked glass slippers, the bones in my mother’s back.

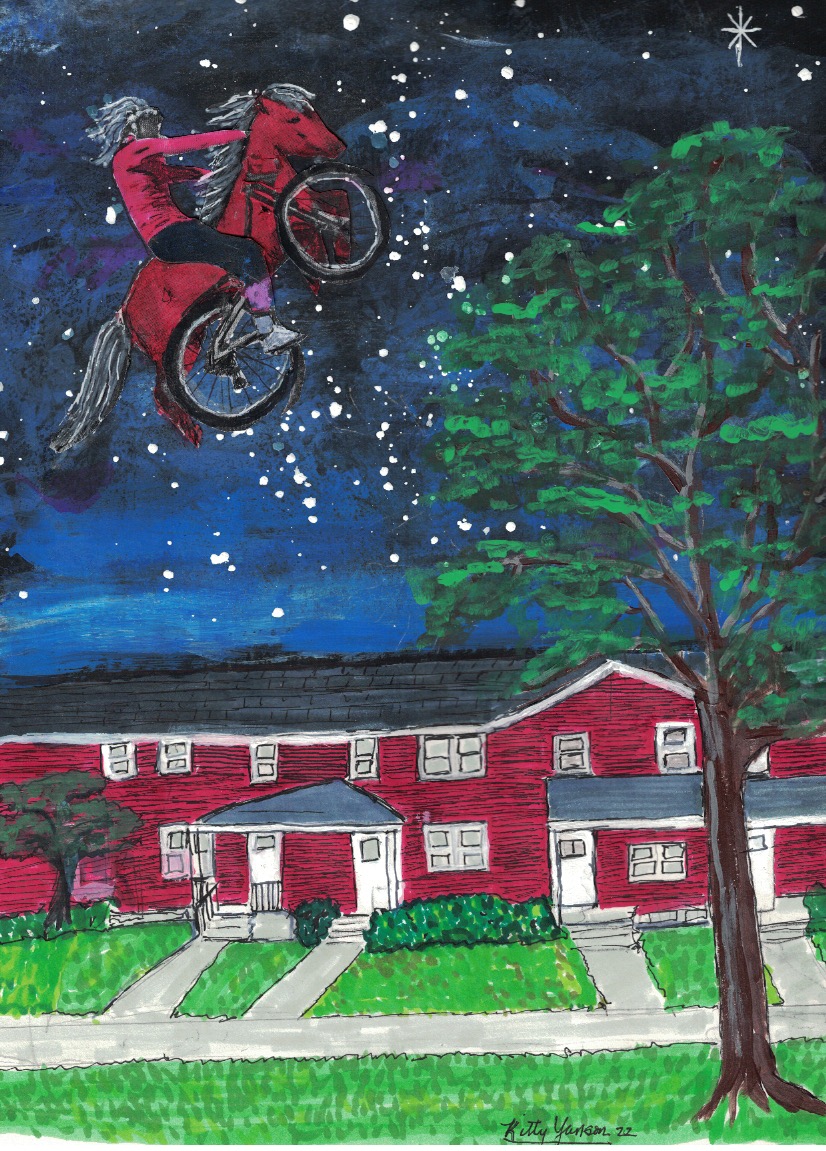

I ride my horse, Tzarina, there. Raucous hooves

are borrowed jokers clacking against her spokes;

for reins, frayed clothes lines tied to handle bars.

Through the stick-ball games, the den of boys beneath

the bridge, the wiffle-headed trolls, I spur

in circles, bend hell, hold my breath, and pass

their puppy stink that whirls from their heads like a smoke

of gnats. I dodge their litter and insults hurled:

“girl,” squashed tin cans, “turd ball.” Fast, clatter fast

down the alley, low in Tzarina’s deep sway, her mane

in my face, her mane as long as August flags

my face with humid air. Like Sunday car

wash water, rush, like whispered sins confessed,

forgotten prayers expelled in a hiss, rush, rush:

the storm drain waits to hear my story told.

Tzarina rears. Hooves turn and slice the sun

to crescents. I will go to heaven when I die.

II.

In Northwood, trees were chosen not for grace

or stateliness, color of bloom, or autumn leaves

but for speed, exuberant growth. Our maple, rank

as Hydra, devoured time, spat seeds, platoons

of wishbones groomed for flight, stripped clean of all

but wings and banzai war cries that whirred the name

of earth in silent troth. My father raked

siege lines, demanded his turf against the Spring,

against these dizzy kamikaze seeds.

Still, some escaped to infiltrate the thatch

or mined beneath the concrete slabs till June’s

slow sun touched off a blast of rootwork, called

to attention stems, blades ready, fixed, alert

to the exigent stand, the requisite shalt be, of trees.

I am traitor. I glean the walks, gather green

from hoods of cars, and raid my father’s heap

of vanquished enemies. Through my fingers I sift

seed-eyes, brows arched in questions that fly unasked,

unpeel their wrinkled lids, un-half their hopes,

eat them, stick them in my ears to hear the wind

as trees do–ocean swarms, shelled whispers trapped–

toss them, watch them spin, twist the whirl-a-gigs

in my hair and call the birds to nest. I make

chains, rosaries to hang about my neck,

pray mystery language swiped from gargled chants

of radio novena priests: hail, fulla grace,

the lurid’s with thee, blessib is the fruit of thy wound,

(nod) Jesus. Wedging seeds up my nostrils, I

become a cross-eyed alien, scream like a cat

with saber teeth so upcurled that when I nod,

I fork up dinosaurs: yes, I kill, yes, I sleep,

I am older than you, more violent, more real,

I am fiercer than shadows street lights force from night.

I will live forever: as long as even Spring.

III.

Some years my father, half accountant, half

a hero, hewed the maple’s head. He said

this was essential discipline to stay

its excrescence. While this giant, panoplied

with leaves, took hostage the harrowed summer sky,

my father sipped inadequate old-fashioneds

and swizzled ambered thoughts of two AM

in Saipan. The officers club: unfinished, undrunk

Jack Daniels, Johnny Walker Reds, the rum

and cokes, the Tanqueray gins with their juniper taint

of evergreen, their tinge of poison faint

enough to immunize, not kill, all mixed

to a punch, doled out to the pilots of rescue flights:

the remains of courage. He had been last called.

Home now, he exchanged his pilot wings for wood

saws, planned the strategic moment, watched

the autumn’s yellow peril fade, the day

of weakness, the tree’s double timed-death

in December. Then struck. Deposed, the maple endured

through winter, its frozen cyclone and hardened rhyme

of seeds exposed by the oval cut, now crowned

with tar. A dark fist clenching life, it raised

its sleeping challenge: Know before whom you stand.

IV.

In this tree’s hesitation, stars are spawn, unschooled

until my father’s Sistine finger calms

the obstreperous moon to trace across the black

construction-paper night the forms of cartoon

stick things, connecting dots in this puzzle book

in constellations. He takes my gloved hand, lines

my sight with his” “Polaris. That’s the North

Star. Find it and never lose your way at night.

See? It leaps from the cup like a bubble that stings

your nose, an effervescence. Orion’s there

with his club, a hunter chasing pigeons–girls

they were once, the Pleiades, seven sisters loved

so hotly, so hopelessly pursued that a star

was born in Orion’s armpit, Beteljuice,

the gleaming sweat of eternal war. And there

is Lyra, the harp of Orpheus, playing the gods’

stone silence, while the swooping eagle, Vega, tunes

the strings, ensnaring those who listen, who spy,

on gods, with ears against the door of night.”

In a room upstairs, my brother cries in straight

unyielding arrows until my mother bends

them, coaxes them with lullabies to curl

in her lap like willow withes. The Polish words

I do not understand, but I know the tale

her body speaks: the phrase of powdered warmth,

the grammar of arms, the syntax of fluent skin.

the order of breath, the spelling of pulse. I’ve walked

the labyrinthine passages, open courts,

the columned temples, the pillared caves of sleep

against her breast. The winding trail of dreams.

Outside alone, I look to find a tale

of crooning mothers, but legends always flex

in unrelenting waves among the stars,

the bones of heroes that led my father home.

They leave no pages blank, without a word

to colonize, to fill with inevitable fact

and purpose, destination. They’ve conquered night.

But I want these stars, against the darkened wall

like shattered apples, to cling with bits of bright

debris, an unswept vacuum, and all the stars

dissolved but one. North Star. In the crook of my sight

it’s the never-closing eye of my motherland,

now foreign: an ache, a throb, a small white cry.

-Kitty Yanson